Korean tools for learners

1. Introduction

I developed KoSeg (Korean segmenter) over the last few years as a tool to help me learn Korean, and although it has many shortcomings, I'm presenting it here in case it might be of some help to others. In brief, KoSeg splits each word in a sentence into a meaning segment and an affix segment. For more information, see below, or go to the Segmenter page itself.

In many cases the output for a word will be equivalent to that from a glosser (or tagger). However, I call KoSeg a segmenter rather than a tagger because in a significant number of cases it performs no disambiguation of the output, and just lists all possible meanings for a word.

KoSaj (Korean sajeon, meaning "dictionary") is the dictionary used to look up the words and affixes. For more information, see below , or go to the Dictionary page itself.

I have created both these resources myself from my own reading and research, but I owe a great debt of gratitude to many authoritative sources for their Korean language knowledge, which I have unashamedly sculpted into something that suited my own purposes. If by doing so I have misrepresented any aspects of the language, I beg indulgence and forgiveness. The tools are based on analysis of around 70,000 words of formal written (original or translated novels, readers, etc) and some less formal spoken Korean (podcasts). Since these texts are under copyright, I cannot make them available here.

Both KoSeg and KoSaj are made available under the GPL3 and AGPL3 - see below for further details.

The dictionary should be useable on a phone, provided you have an internet connection. I am looking at the possibility of doing an Android app to allow offline usage -- if you have any advice to share, feel free!

Note that because both tools are under development, the ouptut you get may differ slightly from that shown in this documentation.

2. Koseg

It is important to emphasise that KoSeg is NOT a translator like Kagi Translate (by far the best Korean-English translation resource), Papago, or Google Translate. It is located in the space between those translation resources and online dictionaries like the excellent Naver offering, in that the main aim is to produce a sense of how the words in a sentence are syntactically related to each other. With a dictionary, you know what the individual words mean (once you remove the affixes attached to them, which is not necessarily easy for a learner), but even then it may not be clear what the overall meaning of the sentence is. With a translator, you know what the overall sentence means, but it may not be clear how the component words contribute to that meaning. KoSeg allows you to review the individual word meanings to work out how that word contributes syntactically to the meaning of the sentence as a whole. I've found KoSeg quite useful in a strongly left-branching language like Korean, where you usually get the topic at the beginning, and a verb at the end, but the relationship of the words in between can be a bit opaque.

The key point here is that KoSeg does not give you a "finished" explanation of the sentence -- rather, it does an automatic dictionary lookup, and gives you the general meaning of the words in the sentence. It is up to you to do a bit more thinking about how those words convey the meaning of the sentence. What I do is get Kagi to translate the sentence so that I know the information being conveyed, and then use KoSeg to relate individual words to that sentence-level meaning.

Usage

On the Segmenter page, enter a Korean sentence into the text box on the left, You can copy and paste a sentence of your own, or use one of the sample sentences on the right. Alternatively, you can just type directly into the text box. Note that your text will be truncated to 100 characters (hangeul syllable blocks or Roman characters) to prevent server overload, and only common characters that you are likely to meet in ordinary text are permitted. You can input other characters such as the "booktitle" characters『』《》, but these will be converted to quotation marks. Also note that currently KoSeg will refuse to process text that includes hanja (Chinese characters) -- they need to be removed from the input text in order for it to be accepted. If you have an English translation for your sentence, you can attach it to the Korean sentence using § (on the standard Ubuntu keyboard, this can be typed using AltGr+Shift+W), and that will be printed out as well, at the bottom (see the sample sentences for examples).

Once the text is in the box, press the "Segment it!" button. KoSeg will then produce a printout on the right, with each word in the sentence stacked vertically.

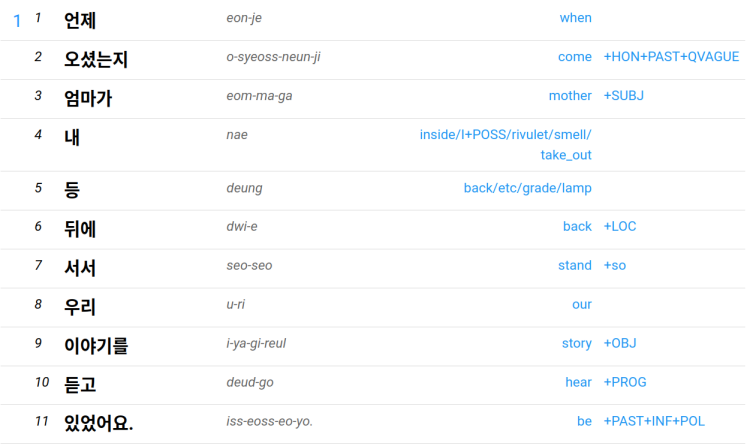

The following image shows the output for the sentence "언제 오셨는지 엄마가 내 등 뒤에 서서 우리 이야기를 듣고 있었어요." (from 할머니 테왁 hal-meo-ni te-wag, by 김종배 gim-jong-bae).

The output includes a number for that sentence in the input, and then a number for each word in that sentence, followed by the word in hangeul. Against each word (across the row) there will be a romanisation (see below), then a meaning for the word, and a meaning for the affixes (if any) attached to the word.

Meanings

The entry for the meaning consists of the "prime" meaning for each word. The prime is a single meaning that best sums up the constellation of meanings for any given word. This is done purely in order to keep the output manageable, and it should be said that the prime meaning is somewhat subjective. However, clicking on the prime meaning will open a popup showing the full KoSaj dictionary entry for that word, which allows you to view the range of meanings associated with that word. One of those other meanings may be more appropriate for the word's usage in the sentence. If the prime meaning seems not to fit well into the sentence, it's a good idea to click on it to show the popup, since that will offer more options for the meaning. Click the "Close" button at the top right to close the popup.

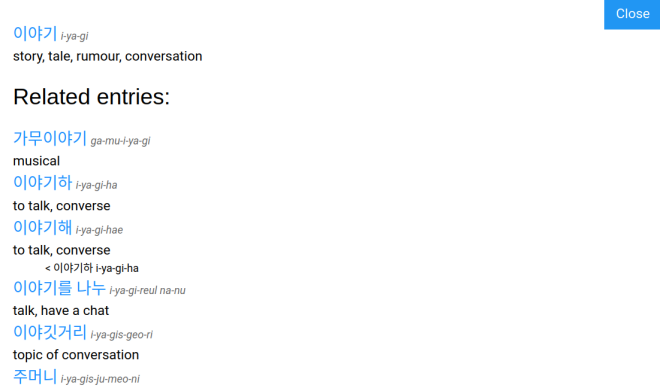

For instance, clicking on the word "story" against 이야기를 i-ya-gi-reul will show the following:

One of the other meanings listed there, "conversation", is more appropriate for this sentence than the prime meaning, "story". Since the aim of KoSeg is to clarify the affixes used, the prime meaning is often a verb with additional affixes. For instance, 고픈 go-peun will give the prime meaning as "be_hungry+DESC", ie a descriptive based on 고프 go-peu. In such cases, clicking on the prime meaning will give a more "English" translation, in this case "hungry, famished".

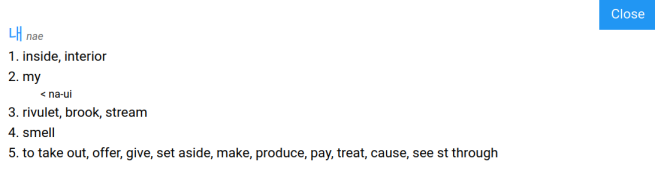

In some cases, words will have multiple meanings, and in that case the primes are listed in a group. This is most common with shorter words. In the above sentence, 내, nae, and 등, deung, have multiple meanings. Clicking on the group will give all the meanings separately, as with the popup for 내:

In this case, the choices for 내 nae and 등 deung that make most sense are "I+POSS" (equals "my") and "back", so that 내 등 뒤에 means "behind my back" (lit. at the back of my back).

Affixes

I use the term "affix" instead of "ending" or "suffix", because although many affixes usually appear at the end of the word, it is not unusual to have further affixes attached to these normally "word-final" affixes. To take one example, the plural affix -들 -deul very often occurs as the last item in a word, but is frequently followed by other affixes: -들처럼 -deul-ceo-reom, -들하고도 -deul-ha-go-do, -들한테만 -deul-han-te-man, -들만큼이나 -deul-man-keum-i-na, and so on.

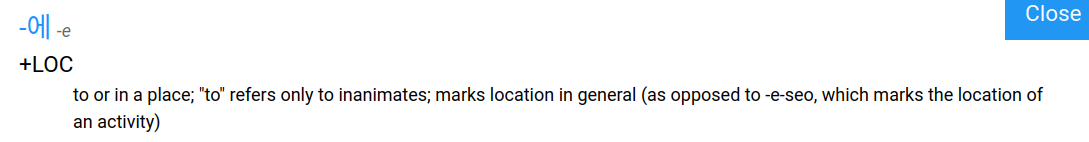

The final column of the output gives the affixes attached to the word. All affixes are marked in glosses with an initial + (plus sign). As with the prime meanings, you can click on the affixes to open a popup. If an affix sequence has multiple meanings, they will be listed in a group, and the popup will show each of those meanings. In some cases (as with +LOC in this example), the affix entry in the popup may have additional notes explaining general meaning:

So far as possible, affixes are broken down into the main semantic components. For instance, in the sentence example above, the word 오셨는지 o-syeoss-neun-ji, is segmented as the verb 오 o, "come", with attached affixes -셨는지 -syeoss-neun-ji. This affix sequence consists of -시- -si- (honorific), -었- -eoss- (past tense), and -는지 -neun-ji (an interrogative expressing uncertainty or inquiry). The affix sequence is therefore listed as +HON+PAST+QVAGUE (see below for the meaning of abbreviations), so that the first two words (언제 오셨는지) can be translated as "I wonder when she came" or "I'm not sure when she came".

That gives a viable translation for the whole sentence: "I'm not sure when she came in, but my mum was standing behind me, listening to our conversation."

At present, some 1,600 affix sequences are listed in the dictionary, and although many of these are variants (eg, with or without the polite affix -요 -yo, the plural affix -들 -deul, the honorific affix -시 -si, and so on, the variety and number of affix sequences is one of the reasons why Korean makes such demands on the learner.

The Affixes page on this website lists the components of all affix sequences in the dictionary. Clicking on a component will show all the affix sequences it occurs in, and clicking again will hide them. It is worth noting that not all affix sequence variants have been listed yet in the dictionary, so (for example) a sequence following a vowel-final word may be missing, while its equivalent following a consonant-final word may be listed -- this is a function of whether or not it has been enountered in my reading!

Affix abbreviations

Affixes are divided into two types for glossing. The first type uses general ideas as glosses, and are written in capitals, eg +PAST, +REALISE, +SUGGEST. The second type uses specific English words as glosses, and are written in lower-case, eg +so, +must, +also . This is an ad hoc and somewhat artificial distinction, and may be revised at some point in the future.

Abbreviations which are not full words are listed here: ADV adverb, AFF affirmative, CONT continuous, DESC descriptive (adjective), FUT future, FUTDEF future definite, HON honorific, HORT hortative, HYP hypothetical, INDIC indicative, INFIN infinitive, INST instrumental, INT interrogative, L L-form (future participle), LOC locative, NEG negative, OBJ object, PL plural, PLUPERF pluperfect, POL polite, POSS possessive (genitive), PROG progressive, PROP propositive, QQUO question quotation (indirect interrogative), QUO quotation (indirect affirmative), QVAGUE vague question, SUBJ subject.

Partial segmentation

A complete segmentation of a word depends on (a) the base word being listed in the dictionary, and (b) its affix sequence being listed among the affix sequences in the dictionary. Either of these conditions may not be met, in which case you get a partial segmentation, or none at all.

3. KoSaj (Korean dictionary)

KoSaj (Korean 사전 sa-jeon, "dictionary") is the dictionary used to look up the words and affixes. When I started learning Korean, I wanted to use a digital dictionary as input to a Korean segmenter to help me understand the structure of Korean sentences more easily, but there seemed to be no simple but comprehensive free (as in freedom) electronic dictionary of Korean available: the ones I could find had limited numbers of words, or there were serious issues around content quality. KoSaj fills the need for a curated source of words for KoSeg, where the entries follow a logical structure, with the English meanings being consistent and natural. This is an ongoing process, of course, and more remains to be done on this front.

Usage

The Dictionary has its own page, but you can also search from any page on the website. Use hangeul in the Korean box, English in the English box, and romanisation in the Romanisation box (here, you need to use hyphens to separate the syllables as written in hangeul, eg "neo-mu" instead of "neomu"). Currently, you can only search for single words, not phrases.

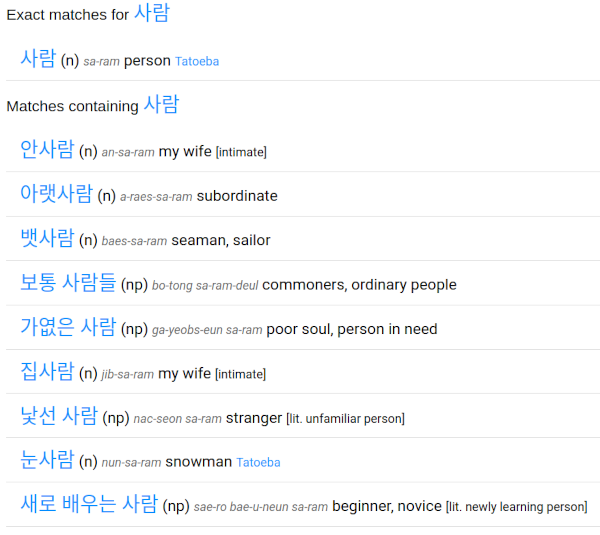

The results are returned in two groups -- the first contains exact matches for your search term, and the second contains matches which contain your search term. Entries use the following format: the Korean in hangeul, the part of speech in brackets, a romanisation of the hangeul, the English equivalent(s) of the Korean, with any notes about the word following in square brackets. The image below shows part of the results for 사람 sa-ram, "person".

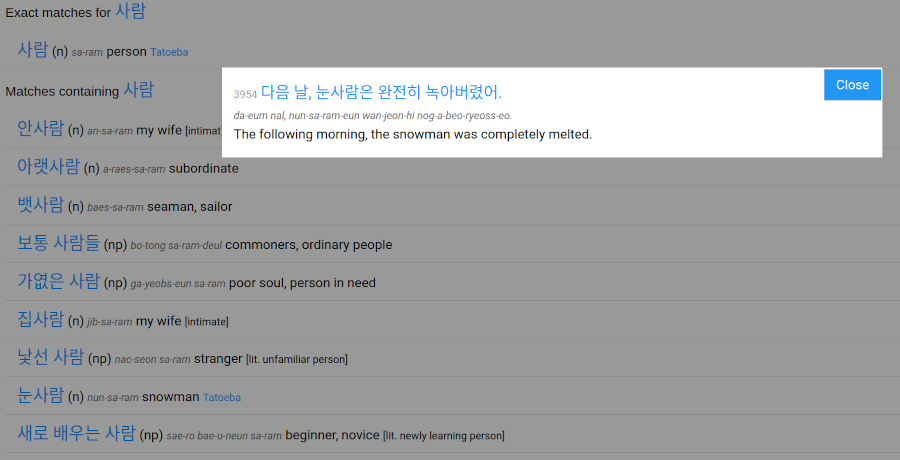

Clicking on the "Tatoeba" link beside an entry will produce a popup offering citations for that entry in (an older version of) Tatoeba. These are less useful for monosyllables, where there is no way to distinguish between homophones. The image below shows the citation for 눈사람 nun-sa-ram, "snowman". Use the "Close" button in the top right of the popup to close it.

Ideally, it would be nice to include other citation sources, but they would need to be under a free license.

Coverage

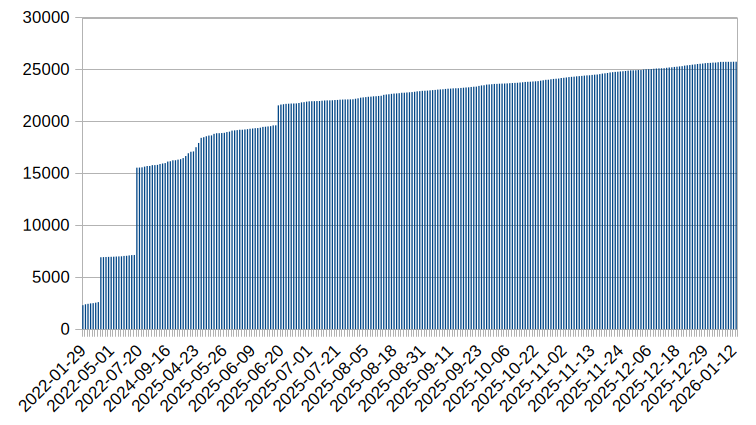

I began compiling KoSaj in 2022 from my own vocabulary lists, and then later that year added larger tranches from whatever online sources I could find: words from TOPIK lists posted on the web (2022-04-10), and words from cc-kedict/Wiktionary (2022-07-15), although both of these required heavy editing subsequently. Ongoing additions have been made over the following years (see the chart below), especially in 2025, when there was a further large addition deriving from a script I wrote to generate infinitives (2025-06-19). The dictionary currently contains almost 22,000 entries (plus another 4,000 entries for infinitives, stem variants, etc), but I still find that around 4% of anything I read consists of words that are not in KoSaj (and that can rise to 15% in more specialised or literary texts). So there's still a long way to go, and my aim is to continue expanding the dictionary, with CC-CEDICT as an inspiration.

Structure

The table below sets out the fields of the dictionary table ("vocab").

| Column name | Data format | Description |

|---|---|---|

| id | integer | Unique id number (primary key) for the entry. |

| korean | character varying(250) | The Korean word in hangeul. |

| english | text | A range of English meanings for the word. |

| rom | character varying(250) | A romanisation of the Korean word (see below). |

| notes | text | Information on derivation or usage, or background cultural information. |

| pos | character varying(10) | Part of speech of the word. This is only an approximation, since Korean POS categories do no map neatly onto English ones. |

| prime | character varying(250) | A single meaning that seeks to sum up the constellation of meanings for the Korean word. Note that in order for the prime meaning to appear correctly in the output, all spaces in the word must be replaces by underlines(_), eg "be involved in" → "be_involved_in". |

| origin | character varying(10) | Source of the Korean word, only used to note the source of major imports. |

| added | date | The date the Korean word was added to the dictionary. Up to 2025-05-21, commit dates are used as a proxy for the date of entry, and thereafter the actual date of entry is used. |

My offline version also outputs Yale transcription as well as (or instead of) revised romanisation, but that is not offered here -- if there is demand I can add it.

The usual citation form for Korean verbs uses a final -다 -da affix, eg 움직이다 um-jig-i-da "to move, be in motion". In order to simplify the operation of KoSeg, this affix is NOT included in the KoSaj entries for verbs. The entry for the above example will therefore appear as 움직이 um-jig-i "to move, be in motion". The entry is still marked as a verb in two ways, though: the POS will always be "v", and the English meaning will always begin with "to".

As noted above, the dictionary contains entries for about 4,000 (to date) derived forms. These include:

Infinitives.

4. Romanisation

The romanisation seeks to follow the Revised Romanisation (국어의 로마자 표기법 han-gug-ui ro-ma-ji pyu-gi-beob) devised by the Republic of Korea’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism in 2000, with some minor changes to simplify round-tripping between hangeul and romanised text. hangeulise()

Hangeul table5. Licensing

Both KoSeg and KoSaj are free software available under the Free Software Foundation's General Public License version 3 or later, and the Affero General Public License version 3 or later. These licenses mean that (a) you can freely change the code to suit your own purposes, and even redistribute that changed version if you wish (with the proviso that you MUST also use the GPLv3 for that changed version), and (b) you can rewrite the web interface to suit yourself, but that rewritten version MUST also be made available under the Affero license. Ideally, you would also give me a copy of any changes or additons that you make, so that they can be incorporated into this original version, but that is not a necessary condition for editing the code or interface as you see fit. The code and dictionary can be downloaded from XXXX this Git repository.

6. Local installation

If you wish, you can set up KoSeg and KoSaj on your own PC or laptop. Both tools have been developed on Linux (Ubuntu 24.04 LTS), but they should run on legacy operating systems too, though you might need to do some tweaking to fit how those OSs do things.

You need first to install the Apache2 webserver, the PHP scripting language, and the PostgreSQL database management software. phpPgAdmin is also useful for oversight of the database. Packages for all of these are usually available via your Linux distro's built-in package manager.

Clone the XXXX Git repo to get a copy of both tools. Then load the database (dbs/kosajseg.sql) into PostrgreSQL, and set up a virtual server in Apache2 so that you can access the web interface when you enter "http://kosajseg" in your browser's address bar. If you want to edit the dictionary, I would recommend DBeaver, since it allows multiple edits to be made on one result set.

If you run into problems setting this up, contact me -- I can give you further details. My ability to help with legacy OSs, though, is very limited, since I haven't used one since 2005.

7. How KoSeg works

This is stuff you probably don't need to read unless you want to contribute to development.

The PHP script webseg.php does most of the work. First, it makes some changes to the input string to handle punctuation, and then truncates the string to 300 characters and checks that it contains only allowed characters. Then the input string is segmented into sentences, and each sentence is processed in turn.

Romanisation

The sentence is romanised using the romanise() function, which looks up each jamo block in the kosajseg database's hangul table, and returns the romanisation for that block, with each block being separated by a hyphen. The romanisation seeks to follow the Revised Romanisation (국어의 로마자 표기법 han-gug-ui ro-ma-ji pyu-gi-beob) devised by the Republic of Korea’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism in 2000 (see below). Further changes are then made to ensure that the romanised words can be properly handled. It is important to note that the operation of the segmenter depends entirely on the romanised version of the sentence rather than on the hangeul original, since (for me) it is easier to write regular expressions in Roman script. The corollary is that changes to the romanisation will need knock-on changes elsewhere in the segmenter.

The script parse/linespan_edits.php then adjusts the romanisation to allow for affixes to be segmented based on a following word. For instance, hal-su, "able to be done" → ha-l su. Next, the romanised sentence is split into words (tokenised), and the script parse/word_span_edits.php adjusts the romanisation of the individual words to allow for affixes to be segmented. For instance, gal-geo-ye-yo, "will go" → ga-l-geo-ye-yo.

Lookup

The next step is to look up the words and the affix sequences in the dictionary, using the process_word() function. First, the words are separated from the affixes using the segment_word_prioritise_words() function. If the word contains digits, they are split off as a "word", with the remainder being considered an affix sequence. For instance, 4ho-seon-eul, "Line 4" → 4 (word) +ho-seon-eul (affixes), or 170weon-ib-ni-da, "it's 170 won" →170 (word) +weon-ib-ni-da (affixes) Otherwise, the function seeks to find the longest matching word in the database's vocab table, and considers anything following that as an affix sequence. (An alternative approach, exemplified in the segment_word_prioritise_affixes() function, seeks to find the longest matching affix, and consider anything before that the word, but in practice this is too aggressive, and produces a less appropriate segmentation.)

The finding process works by first checking whether the entire word is in the database, and if there is no entry, it removes the final syllable and checks again. If there is still no entry, the penultimate syllable is removed and the check is performed again. The end-syllables are progressively eaten away until an entry matching the word is found, and at that point the sequence of end-syllables is considered an affix sequence. If this process results in no entry at all being found, the original romanisation is passed through to be checked as a compound noun (see below).

The found word is then looked up using the multicol_lookup() function, which returns various attributes of the word (romanisation, prime meaning, and part of speech). Where more than one entry matches the found word, this data is concatenated for the output. The affix sequence is looked up using the singlecol_lookup() function, which returns the prime meaning. Again, multiple entries for the affix sequence are concatenated for the output.

Compound nouns

If no entry was found for the word, it is passed to the segment_compound() function, on the assumption that the unknown word may be a compound noun made up of several shorter nouns that are already in the dictionary, even though the compound is not. Korean tends towards combined compound words (like German) instead of spaced or hyphenated compound words (like English). Examples are 운전면허증 un-jeon-myeon-heo-jeung, "driving licence", 쇼핑지역 syo-ping-ji-yeog, "shopping district", or 반지값 ban-ji-gabs, "the price of a ring".

The function first checks that there is more than one syllable left, and then checks whether the first three syllables of the word match an entry in the dictionary. If a match is found, that is stored as a word, and the next three syllables are checked for a match. If no match is found, the function checks whether the first two syllables match an entry in the dictionary, and stores that if it is found. A limited number of affixes are also allowed for (though this may not be foolproof). If no two-syllable match is found, the original romanisation is passed through to be printed in the output.

The above three examples (including some sample affixes) would be segmented as follows:

운전면허증이 un-jeon-myeon-heo-jeung-i → driving⼁licence (=driving licence) +SUBJ

쇼핑지역을 syo-ping-ji-yeog-eul → shopping⼁region (=shopping district) +OBJ

반지값 ban-ji-gabs → ring⼁price (=the price of a ring)

If desired, the compound nouns can then be added to the dictionary as entries in their own right (as these three have been).

For some compounds, adding new entries may not be appropriate, eg

전주전통술박물관 jeon-ju-jeon-tong-sul-bag-mul-gwan Jeonju⼁traditional_alcohol⼁museum

The algorithm above is not perfect, because if the initial cut fails, the rest of the segmentation also fails.

For instance, 귤공방 gyul-gong-bang gyul-gong⼁room, should be gyul⼁gong-bang → tangerine workshop

In such cases, you can try manually segmenting the word in the input box by placing a space between characters:

Thus 귤 공방 gyul gong-bang → tangerine workshop

Output

Following dictionary lookup, the output is then adjusted, using parse/adjust_parse.php, to prune alternative meanings, or finetune the meaning offered. For each found word, a number of attributes (the word itself, its part of speech, its prime meaning, the original romanised affix sequence, and the affix sequence after affix lookup) are recorded. A series of regular expressions then uses the attributes of the word, along with the attributes of the words before and after it (ie a three-word window) to adjust the meanings, the aim being to select a relevant meaning from among a concatenated group of meanings (especially common in short one-syllable homophones), or to change the prime meaning to one that is more relevant to the context.

Examples of the former:

if ($uword=='sog' and preg_match($nmarkers, $uaff)) { $uprime="interior"; } Choose the nominal homophone when noun-related affixes are present.

if ($uword=='sog' and preg_match($vmarkers, $uaff)) { $uprime="be_deceived"; }Choose the verbal homophone when verb-related affixes are present.

Examples of the latter:

if ($uword=="jeos-gal" and $unext=="hu-reu-reug") { $uprime="mouthful"; } Change the prime meaning shown for jeos-gal from "spoonful" to "mouthful" when the next word is hu-reu-reug, an ideophone for "slurping".

if ($uword=='man-nyeon' and $unextpos=="n") { $uprime="eternal"; } When preceding a noun, choose the adjectival meaning for man-nyeon (lit. "10,000 years") instead of the nominal one ("old age").

In effect, the above system is a basic constraint grammar, and the limited attibutes and three-token window work surprisingly well. However, although it is lightweight and obviates the addition of a CG3 software package, it has limitations. The main one is that it does not select particular options in a concatenated group of homophonic prime meanings, but simply overwrites them with a preferred meaning. Neither can it refer farther back or farther forward than the three-token window, whereas CG3 is much more versatile in this respect.

After these adjustments, the words are reassembled into a sentence again, and printed out as a HTML table along with the original hangeul sentence using the convert_array_to_table() function.

8. Shortcomings

I find KoSeg useful for my purposes, but at the time of writing it has a number of undeniable shortcomings.

Aux verbs are added as part of the affixes. Again, not ideal.

I would like to extend these notes in the future, and there may also be a need to review and possibly standardise some of the affix tags. As noted above, more work needs to be done on normalising the affixes. and it is possible that if and when the affixes are normalised, this distinction may be removed, affixes re-glossed, etc.

Hard to deal with names.

Punctuation less common. No hyphens.

As it stands, the dictionary is very much a work-in-progress -- structure etc may change depending on future needs. If you have words to contribute, or corrections to make, please feel free to contact me -- you can use "kevin" for the name, with the domain "dotmon.com", joined by the curly thing.